Explorar los efectos más profundos de más aranceles

Potencialmente mayor producción estadounidense, pero se esperan precios más altos y menos cooperación global

Al entrar en 2024, la pregunta en la mente de muchas personas era qué tan pronto la Reserva Federal de los Estados Unidos y otros bancos centrales comenzarían a recortar las tasas y si se moverían al unísono. Ahora, entrando en 2025, un enfoque significativo está en la naturaleza y magnitud de los aranceles estadounidenses propuestos y cómo reaccionarán la economía de los Estados Unidos, y el mundo.

Por supuesto, muchos de los detalles que rodean los aranceles siguen sin decidirse y seguirán siendo así hasta después de que el presidente electo Donald Trump asuma el cargo en enero y se anuncien nuevos aranceles. Sin embargo, aun así, los expertos dicen que la historia, y la economía, pueden ayudar a esbozar cómo puede ser el camino a seguir.

¿Los aranceles harán que la inflación vuelva a subir? ¿Qué pasa con el crecimiento?

En general, no es el uso de aranceles en general lo que preocupa a algunos economistas, sino más bien cuán amplios o grandes podrían ser los aranceles. Durante su campaña, las propuestas de Trump incluyeron la imposición de una Arancel general del 10 al 20 por ciento sobre todas las importaciones, con aranceles adicionales del 60 al 100 por ciento sobre el bienes importados de China, y un arancel del 25 al 100 por ciento sobre mercancías de México-si el gobierno mexicano no refuerza la frontera entre Estados Unidos y México. Sin embargo, a fines de noviembre, propuso un arancel del 25% sobre los bienes importados de México y Canadá y un arancel del 10% sobre las importaciones de China.

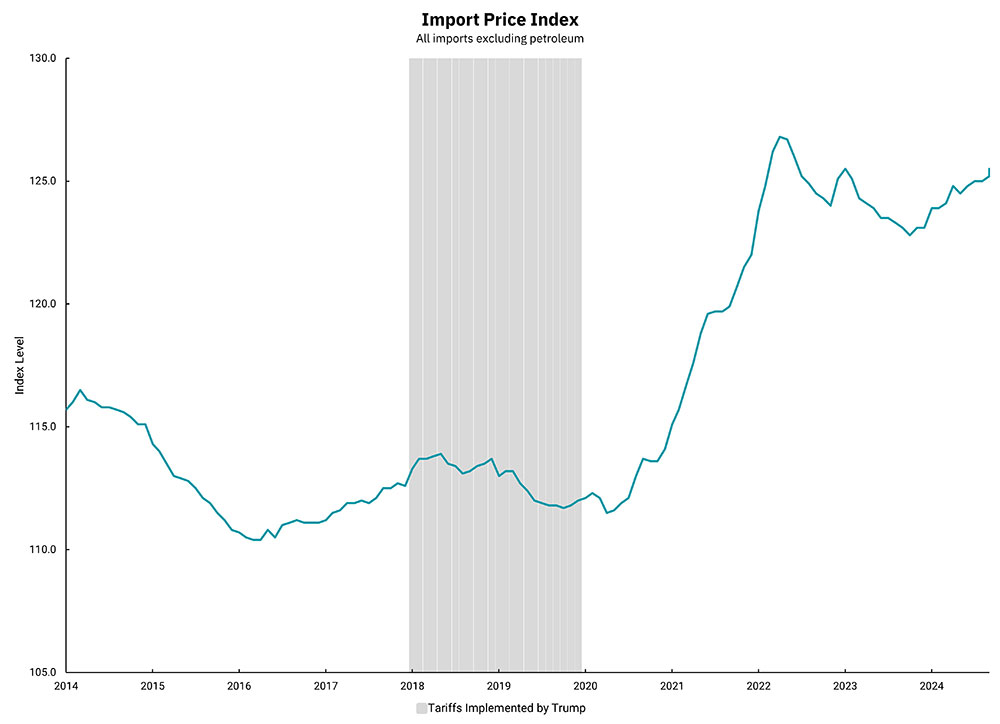

Leyenda: Los aranceles anteriores del ex presidente Trump tuvieron menos impacto en los precios de importación que la pandemia de Covid.

Como director de inversiones de BOK Financial® Steve Wyett "Los aranceles específicos pueden ayudar a evitar que China haga dumping de acero en el mercado global, por ejemplo, o algo de esa naturaleza, pero el uso generalizado de aranceles probablemente causa tanto daño económico como ayuda.

"Si estás usando aranceles para proteger a los productores nacionales, inevitablemente, lo que estás diciendo es: 'Voy a aumentar el precio de este bien extranjero que se puede importar más barato, para que se pueda hacer aquí'. Sin embargo, eso significa que ahora se les pedirá a los consumidores que paguen un precio más alto por el bien, ya sea pagando el arancel sobre lo que se importa o pagando un precio un poco más alto para que un productor nacional produzca el bien. El productor nacional lo va a fijar lo más cerca posible del precio arancelario", explicó.

Y así, los aranceles amplios tienden a ser inflacionarios desde el punto de vista de los precios, hasta el punto de que destruyen la demanda, continuó Wyett. "Entonces, de repente, tienes un crecimiento económico más bajo".

Al mismo tiempo, los defensores de los aranceles amplios argumentan lo contrario. Por ejemplo, la Asociación de Comercio Internacional de Washington (WITA), una organización sin fines de lucro y no partidista que incluye al presidente y CEO de la American Apparel & Footwear Association como presidente de su junta, publicitó un modelo comercial que predice que los aranceles amplios beneficiarían a los consumidores y empresas estadounidenses de múltiples maneras.

Específicamente, el modelo 2022 analiza el impacto de un aumento arancelario de ingresos del 15% en todos los bienes importados, y un aumento arancelario del 35% en algunas importaciones que son significativas por razones económicas o por "resiliencia nacional", como las importaciones de países con no acuerdo de libre comercio (NFTA). Con ellos en su lugar, el modelo predijo un aumento del 7% a la economía de los Estados Unidos, 10 millones de nuevos empleos, un 10% en el ingreso familiar ajustado a la inflación y $ 603 mil millones generados en ingresos federales.

Sin embargo, el modelo utiliza cifras arancelarias que difieren significativamente de las que Trump sugirió durante su campaña. Para poner todos estos números en perspectiva, hay que retroceder casi 200 años a 1830 cuando se impuso el arancel más alto en la historia de los Estados Unidos, un impuesto de casi el 62% sobre todas las importaciones sujetas a impuestos, y recibió una fuerte oposición política dentro de los Estados Unidos. El segundo arancel más alto fue la Ley Arancelaria 1930 Smoot-Hawley, que aumentó alrededor de 900 aranceles de importación en un promedio del 40% al 60%. Como señaló Wyett, se cree que este acto fue un impulsor de la Gran Depresión, "pero no creo que estemos en la misma posición ahora", agregó.

¿Cómo reaccionarán otros países?

Una de las razones por las que se cree que la Ley Arancelaria Smoot-Hawley ayudó a desencadenar la Gran Depresión es debido a su reducción significativa en el comercio mundial. En respuesta a la ley, alrededor de dos docenas de países promulgaron altos aranceles propios dentro de los dos años posteriores a su aprobación, lo que provocó una caída del 65% en el comercio internacional entre 1929 y 1934.

El presidente electo Trump ya ha indicado que podría proponer aranceles a China y México, lo que podría tener serias implicaciones para las economías de esos dos países.

En cuanto a China: "Si Trump entra y pone esos aranceles en su lugar, entonces eso obviamente tendrá un efecto perjudicial en su economía", dijo Peter Tibbles, vicepresidente senior de comercio de divisas de BOK Financial.

"La economía china ha luchado todo el año a pesar de las numerosas rondas de estímulo de las autoridades para ayudar a impulsar el crecimiento", explicó. "A medida que la clase media se desarrollaba y millones de trabajadores buscaban nuevos empleos de fabricación, los conglomerados inmobiliarios chinos construyeron megaciudades masivas para servir como centros para nuevas fábricas e industrias. A medida que el mercado inmobiliario se saturó, muchas de estas megaciudades permanecieron deshabitadas y esto ha demostrado ser un lastre para la economía y las empresas propietarias de los complejos de apartamentos que se suponía que albergarían a millones de trabajadores".

A su vez, la reacción de China a los altos aranceles estadounidenses también podría afectar el mercado energético, dijo Dennis Kissler, vicepresidente sénior de operaciones en BOK Financial. "En represalia, podrían venir en contra de las importaciones de crudo de Estados Unidos en su país. También debilitaría su economía. Recuerde que son el mayor importador de crudo, por lo que si debilitamos su economía, probablemente reduciría la demanda china de crudo, y eso será un problema".

Sin embargo, hasta que conozcamos más detalles sobre la política arancelaria de Trump, será difícil determinar el efecto que estos aranceles tendrán en las economías afectadas y, de hecho, si algún país toma represalias con sus propios aranceles. "Obviamente, va a afectar el comercio, pero la forma en que afecta el comercio puede ser muy diferente, dependiendo de las políticas específicas", dijo Tibbles.

2025 Perspectivas

Un nuevo año a menudo se asocia con la transformación. Aun así, el grado de cambio que se avecina en 2025 parece inusualmente grande para los Estados Unidos, con posibles cambios en la política comercial, la inmigración, la regulación y más. El equipo de administración de inversiones de BOK Financial ha preparado su perspectiva de los 2025 mercados como un informe descargable, artículos complementarios y un seminario web grabado.