El resurgimiento de la manufactura estadounidense

Las exenciones fiscales, los aranceles y las preocupaciones de seguridad nacional están impulsando una nueva era de inversión industrial

Este artículo forma parte de nuestra próxima Perspectiva anual de los 2026 mercados. Pulse aquí para visitar nuestra página web de Outlook y registrarse para la discusión en vivo, que se llevará a cabo el 15 y 2026 de enero a las 11 am CT.

PUNTOS CLAVE

- Los incentivos fiscales federales, los aranceles y la inversión directa del gobierno están impulsando una nueva era de crecimiento industrial en Estados Unidos.

- La relocalización de sectores clave, como los semiconductores y los productos farmacéuticos, tiene como objetivo fortalecer la resiliencia de la cadena de suministro y la seguridad nacional.

- La relocalización podría impulsar el PIB y crear empleos, pero los costos más altos y la escasez de mano de obra siguen siendo desafíos potenciales.

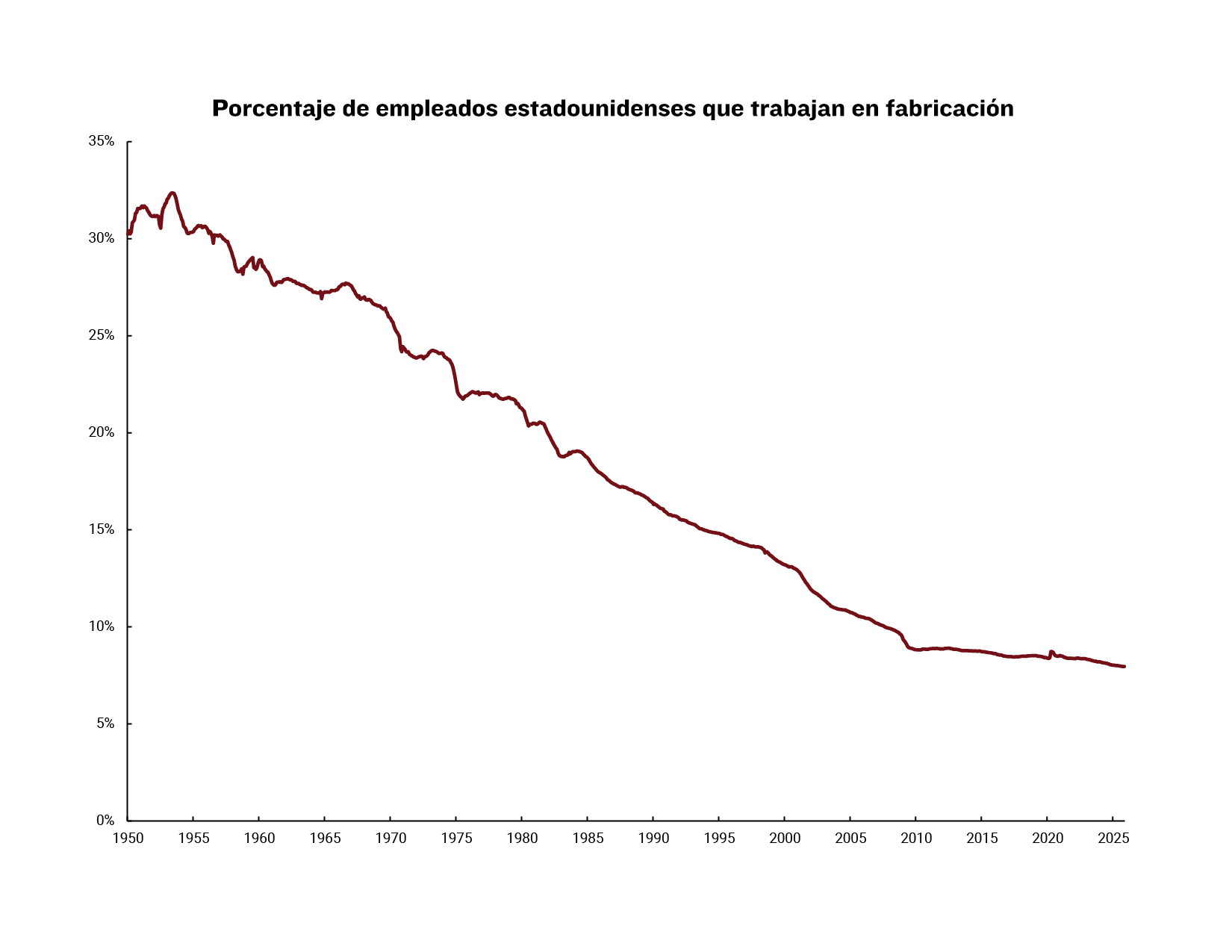

Durante décadas, la manufactura estadounidense estaba en declive a medida que la globalización empujaba la producción en el extranjero, vaciando el Cinturón del Óxido y empujando a los trabajadores estadounidenses en todas partes hacia trabajos de cuello blanco. Ahora, sin embargo, la manufactura estadounidense puede estar en camino a un regreso, impulsada por una convergencia de consideraciones corporativas y políticas.

El impulso hacia la relocalización de la fabricación de bienes clave, como semiconductores, productos farmacéuticos y equipos médicos, así como equipos y tecnologías relacionados con la defensa, se deriva de las lecciones aprendidas durante la pandemia, así como del deseo de asegurar el crecimiento económico y la seguridad de los Estados Unidos en medio de Desglobalización, dijeron expertos de BOK Financial®.

Creen que el comercio y esta revitalización del sector manufacturero de Estados Unidos probablemente impulsarán el crecimiento económico en 2026 y son cautelosamente optimistas de que la relocalización de la manufactura, junto con los avances en inteligencia artificial (IA), podría acelerar el crecimiento y beneficiar a los mercados financieros durante el año.

"Cuando pienso en lo que la administración actual ha hecho para atraer empresas para operar aquí en los Estados Unidos, veo muchas iniciativas favorables a los negocios: incentivos fiscales, aranceles e inversión directa en industrias vinculadas a la seguridad nacional: semiconductores, metales y minería. Esa es una clara señal de que estos sectores necesitan prosperar", dijo Brian Henderson, director de inversiones en BOK Financial.

De hecho, la política federal se ha convertido en un impulsor clave del floreciente resurgimiento de la manufactura estadounidense. Las tasas impositivas corporativas permanentes del 21% dan a las empresas confianza para invertir, mientras que las nuevas reglas que permiten el gasto inmediato de los costos de construcción de las instalaciones, en lugar de la depreciación de décadas, son un "cambio de juego para el análisis de costo-beneficio", dijo Steve Wyett, director de estrategias de inversión de BOK Financial. Mientras tanto, los aranceles también han empujado a las empresas a repensar el abastecimiento global. "El mensaje es claro: no quieres pagar un arancel, producirlo aquí en el país", señaló.

Además, Washington está respaldando industrias estratégicas con inversión directa y legislación como la Ley CHIPS, que ayudó a llevar la fabricación de semiconductores a ciudades como Phoenix, Arizona. "El país está detrás de las compañías e industrias que la administración considera importantes desde el punto de vista de la seguridad nacional", dijo Henderson. La política energética y la desregulación complementan estos esfuerzos, con permisos relajados y reglas simplificadas destinadas a facilitar los negocios y construir la infraestructura necesaria para el crecimiento a largo plazo, continuó.

El declive de la globalización es un catalizador clave para el cambio

Todos estos desarrollos son parte de la desglobalización, es decir, el alejamiento de la globalización, dijeron los expertos. Tras la caída del Muro de Berlín en 1989 y el posterior colapso de la Unión Soviética, la economía mundial se globalizó cada vez más, con la entrada de 2001 de China en la Organización Mundial del Comercio permitiendo aún más a las empresas estadounidenses deslocalizar más empleos a Asia, dijo Matt Stephani, presidente de Cavanal Hill Investment Management, Inc., una subsidiaria de BOKF, NA. Esta economía globalizada creó lo que Stephani llama un "dividendo de paz", que ayudó a mantener bajas las tasas de interés y los precios al consumidor en los Estados Unidos.

Sin embargo, las desventajas de la globalización se hicieron evidentes durante la pandemia de Covid, que expuso la fragilidad de las cadenas de suministro mundiales y los riesgos de una dependencia excesiva de los productores extranjeros. "Nos dimos cuenta de que no fabricamos muchos equipos médicos y productos farmacéuticos en los Estados Unidos", dijo Stephani. "Resulta que la mayoría de estos bienes fueron suministrados por un único proveedor, en muchos casos: China". Los desarrollos geopolíticos agravaron estas preocupaciones. La alineación pública de China y Rusia durante los Juegos Olímpicos de Beijing señaló un cambio hacia un mundo multipolar, planteando preguntas sobre la seguridad de las cadenas de suministro que sustentan tanto la estabilidad económica como la defensa nacional.

Fomentar la relocalización y la relocalización de amigos de estas cadenas de suministro ayuda a mitigar estos riesgos. Como dijo Henderson, "Estados Unidos no siempre es el proveedor de menor costo, pero para industrias vitales para la seguridad nacional, como los semiconductores y los metales de tierras raras, tiene sentido desarrollarlos aquí. Depender de un solo proveedor extranjero crea riesgos que no podemos permitirnos".

Más allá de estas consideraciones de seguridad nacional también se encuentra una dimensión social, según Wyett. "La globalización vació a una gran parte de la clase media de Estados Unidos", dijo. En el pasado, era posible mantener a una familia trabajando en una fábrica, pero a medida que más trabajadores se desplazaban hacia trabajos basados en servicios, que tienden a pagar menos que el trabajo de fabricación, se ha vuelto más difícil para las familias sobrevivir, explicó.

El 1943 de noviembre, durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, el 44% de los empleados estadounidenses trabajó en trabajos de manufactura, según los datos de la Oficina de Estadísticas Laborales de Estados Unidos (BLS). Durante ese tiempo, los ingresos semanales promedio para un trabajador de fábrica estadounidense fueron de $ 44.86 por semana (alrededor de $ 837 en dólares de hoy), según un 1944 Informe del BLS. El salario mínimo federal era de 30 centavos la hora en ese momento, o $ 12 por semana por una semana laboral de 40 horas ($ 224 en dólares de hoy).

En comparación, en el 2025 de agosto, solo el 13.6% de los empleados estadounidenses trabajaban en empleos de fabricación, que pagan un promedio de $ 29 por hora, o $1,160 a la semana por una semana laboral de 40 horas, según las estadísticas de BLS. En otras palabras, aunque el salario de los trabajos de manufactura ha aumentado con el tiempo, el porcentaje de estadounidenses que trabajan en esos trabajos ha disminuido sustancialmente.

Mientras tanto, alguien a quien se le paga el salario mínimo federal de $ 7.25 por hora en 2025 gana solo $ 290 por semana. Eso es solo un poco más que alguien que gana el salario mínimo en 1943 ganado, cuando la cifra anterior es ajustado por inflación.

Con estas cifras en mente, el resurgimiento de la manufactura estadounidense se convierte no solo en chips y sistemas de defensa, sino también en un esfuerzo por revitalizar empleos mejor pagados y productores de bienes. Sin embargo, este movimiento hacia la relocalización no está exento de desventajas. "A medida que traemos más manufactura de regreso a los Estados Unidos, los márgenes corporativos pueden disminuir un poco debido a los costos más altos, pero al mismo tiempo sus cadenas de suministro serán más resistentes y las compañías tendrán más control sobre la producción y distribución", dijo Wyett. Esos costos más altos, a su vez, también pueden trasladarse a los consumidores estadounidenses que ya están luchando con el Efectos compuestos de la inflación.

Lo que está regresando y lo que no

Es muy poco probable que este resurgimiento en la manufactura estadounidense abarque todos los bienes, coincidieron los expertos. Por ejemplo, los productos de alto volumen y bajo margen como camisetas y bombillas probablemente continuarán fabricándose en el extranjero porque no tendría sentido económicamente que las empresas los produjeran en los Estados Unidos a un costo más alto, dijo Wyett.

Esto es lo que es más probable que se produzca en los Estados Unidos, según los expertos:

- Semiconductores: "Los semiconductores son la base de todo", enfatizó Stephani. "Desde teléfonos inteligentes hasta aviones de combate, los chips constituyen la columna vertebral de la tecnología moderna y la seguridad nacional".

- Productos farmacéuticos: "Tener un gran porcentaje de nuestros productos farmacéuticos producidos en el extranjero, principalmente en China, probablemente no sea bueno", advirtió Wyett, citando las vulnerabilidades de la cadena de suministro reveladas durante la pandemia.

- Componentes aeroespaciales, sistemas automotrices avanzados y tecnologías relacionadas con la defensa: Estas son industrias donde la protección de la propiedad intelectual y la seguridad de la cadena de suministro es primordial, dijo Henderson.

Mirando hacia el futuro

La relocalización podría remodelar la trayectoria del crecimiento económico de Estados Unidos. Como observó Stephani, "un resurgimiento en la manufactura aumentaría el crecimiento potencial del producto interno bruto (PIB) y podría ayudar a los Estados Unidos a evitar los desafíos de la deuda". La construcción de nuevas instalaciones probablemente generaría empleo inmediato para oficios calificados y crearía empleos en la manufactura avanzada, amplificando el efecto multiplicador en las economías locales.

Sin embargo, la desventaja de este crecimiento del empleo es que podría exacerbar el Posible escasez de mano de obra de los Baby Boomers que se jubilan y las políticas de inmigración más estrictas, anotaron los expertos. "La oferta de mano de obra es una restricción real", dijo Henderson. "Ya estamos viendo retrasos en la construcción del centro de datos debido a la escasez de trabajadores y la disponibilidad de energía".

Además, los cambios no ocurrirán de la noche a la mañana. "Estas políticas son relativamente nuevas; los beneficios se implementarán durante muchos años", continuó Henderson. Aún así, el impulso es inconfundible. "El acceso a energía confiable y abundante es clave para el crecimiento continuo de nuestra economía, y la administración actual lo sabe", agregó.